- Author: Montanabw, Wikipedia

- Author: Montanabw, Wikipedia

Night Vision

Several years ago, a group of riders from the stables decided to go for a ‘moon ride’. We waited until dark, and then, when the full moon rose into the sky we mounted our horses and rode into the night. Unfortunately that night thick cloud cover blanketed the moon; however, the moon gave enough light for us to see the road. As we turned into the park deep shadows crisscrossed the gravel road, tree silhouettes surrounded us and in places we found ourselves in total darkness. On we rode, three abreast. At times we had a hard time seeing the way; nevertheless, the horses remained calm and enthusiastically moved forward. Their eyes seemed to possess an inner glow as they serenely walked through the darkness. The horses could see far better than their human companions.

A horse’s eye contains cones and rods which are located in the retina or back of the eye. The horse has two types of cones which permit color vision. The rods allow the horse to see black, white and gradations, as well as, enabling the animal to see in dim lighting. The rods are highly sensitive to light and provide excellent night vision for the animal. However, the horse’s eye does not accommodate sudden changes in lighting very well. This slow adjustment to changes in light explains why horses exhibit apprehensive behavior when transitioning from or to different lighting conditions. It takes about 15 minutes for the horse to fully accommodate radical changes in lighting. So when leaving a well lit barn for a night ride remember to give the horse’s eyes time to correct for the dark. Once their eyes have adjusted, horses can see at night about as well as humans can see during the day.

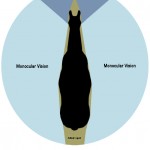

Equine Monocular and Binocular Vision

It’s a rare trail ride that doesn’t involve at least one ‘spook’. After a while it’s not hard to anticipate what objects scare the horse; a huge rock at an intersection between driveways with trashcans and mailboxes on both sides of the road, a large stack of building materials covered by a piece of plastic, whirligigs or flags flapping in the breeze. But why should such mundane objects cause terror to the horse? Most of the trouble stems from how the horse sees the world.

The horse has highly evolved senses which permit a quick escape from predators. The horse’s eye is set far to the side and back on the skull allowing him to see laterally and to the rear with approximately 290 degrees of monocular vision. If you add the horse’s forward binocular vision, the horse can see almost entirely around himself. When the horse holds his head up, there is a narrow blind area behind the rump and directly in front of him. Often if you approach a horse or stand in the horses blind spot he will move his head to see you. The horse’s peripheral vision is highly sensitive to movement, especially movement from behind. It is this ability to detect slight movements or objects within the range of the horse’s monocular vision which contributes to the horse’s flighty behavior.

A few months ago, Karen Sykas and I began training CJ to jump. At first his natural response was to go around or avoid the jump altogether. But since I wasn’t keen on him doing that, he turned back to the jump, raised his head and sailed over the obstacle. Much of CJ’s behavior had to do with the way horse’s see.

The horse has poor depth perception and it is difficult for him to judge the width and depth of a jump. Add to this problem a 2 to 4 foot blind spot directly in front of the horse’s head and you can see why the horse may prefer to avoid the jump. However, if the horse decides to jump the obstacle, he rotates his eyes to engage his binocular vision and focus on the jump. The horse’s binocular vision covers an area approximately 55 degrees around his head and allows the animal depth perception. The horse doesn’t have a focusing lens like humans, instead to correct his vision he must raise or lower his head. This allows light to fall on the retina which is in the lower part of the eye. As the horse rises into the air to take the jump, there is a point where the horse literally can’t see the obstacle.

The more we understand how the horse sees his world the better we can predict and modify the animal’s behavior. Science still has much to learn about equine vision and perhaps in the years to come more interesting facts will be discovered. In the meantime, we can use the knowledge we have to improve our understanding, safety and enjoyment of horses.

Sources: http://www.horsewyse.com.au/howhorsessee.html; http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://thinklikeahorse.org/images/horse%2520vision%25202.gif&imgrefurl=http://thinklikeahorse.org/index- ; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equine_vision; http://www.equisearch.com/horses_care/health/anatomy/nightvision_091003/; http://www.equmed.com/?p=334;http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/vision/rodcone.html;’Basic Training for Horses, Eleanor Prince and Gaydell Colleir, published by Random House, 1979