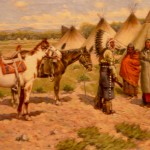

Suddenly in the distance, we saw the Yakima Indians appear at the top of Craig’s Hill. The lead rider wore an eagle feather headdress with an intricate beaded headband and a leather shirt with beaded yoke and fringes. Some Indians wore conical reed hats while others were hatless wearing their thick black hair in long braids. The Indians astride strong noble horses, descended the hill slowly with regal grace, riding single file as they had done since the Ellensburg Rodeo began in 1923. When they reached the entrance to the rodeo arena, their horses turned and were lost from our view. Instantly, loud applause thundered through the grandstands. Finally all was quiet. It was our turn. Our drill instructor, Mr. Hoyt, gave a hand signal for the team to enter the arena. Steward and Johnny pressed their horses into a canter, the flags caught the wind and the rest of the team followed.

Time marches on, many years have passed since I waited for the Yakima Indians to ride down Craig’s Hill in Ellensburg, WA and begin the opening ceremony for the rodeo. A few weeks ago I met with Mary Mix from the Rockwell Museum of Western Art in Corning, NY. We chatted and one thing she told me that stuck was that the viewer brings just as much to the work of art as the artist. Certainly for me the artwork at the museum portraying Indians on horses evokes personal memories as well as the collective images we all share, spread throughout our culture by mass media, movies, TV, and literature. The Rockwell collection traverses a wide range of Western American subject matter including panoramic landscapes, Indians, cowboys, horses and native wildlife. Additionally, the artwork represents an historical viewpoint fixed in the time period from which each piece was created.

“America has always had a love affair with horses, perhaps resulting from their importance in the development of the country,” said Mary as we walked into the Visions of the West Gallery.

“You don’t often hear how important horses have been to our countries growth,” I replied.

“The horse wasn’t always here. They are not indigenous to the North American continent. The Spanish brought horses with them when they came to the New World,” continued Mary.

In all probability the Indians obtained horses from the New Spain province, New Mexico established by Don Juan de Onate y Salazar, the colonial governor. To set up his colony Onate brought with him thousands of domesticated animals including hundreds of mares and stallions. The Pueblo Indians labored on the Spanish colonist’s ranches, learned to ride and work the horses. When the Pueblo expelled the Spanish from New Mexico in 1680, the tribe captured thousands of horses. Some of the horses the Indians captured were traded to tribes on the Great Plains. Now the stage was set for the horse to became an integral part of the Plains Indian’s way of life.

The horse rapidly replaced the dog as beast of burden enabling the Plains Indians to travel with less toil, transport more possessions, hunt the buffalo with greater ease and fight neighboring tribes from further distances. They became skilled horsemen and the horse began to represent wealth; a valuable possession coveted by tribe members.

Mary stopped in front of a huge painting and said, “The “Buffalo Hunt” by William Leigh exemplifies how the Indian hunted. The painting isn’t entirely accurate as the hunter would not have ridden in the middle of the herd. Instead, the rider circled the herd to prevent being crushed by the buffalo. Before the Indians had horses, they stampeded buffalo herds over a cliff in what has come to be known as the “Buffalo Jump”. At the bottom of the cliff, the women and children cut up the dead buffalo and prepare the meat. More animals died than the Indians could use for food and a lot of meat was wasted. Once the Indians acquired the horse they could use more strategic tactics in the hunt. They primarily hunted the cows as the bulls were bigger and extremely dangerous.”

“That’s interesting. It must have taken an expert rider to hunt buffalo,” I replied.

“The horse also needed to be well trained. In fact, the horse an Indian used for the hunt became his most valued possession. An Indian may have had many horses but the one that was trained to hunt buffalo was his prized horse. They notched the horse’s ear to identify their hunting horse from the rest of the herd. Mustangs, hardy, agile and surefooted, were good horses for the Indians and easy to catch. These wild horses lived on the plains with the buffalo and weren’t afraid of them,” said Mary.

“Mustangs are tough little horses and smart too,” I said.

“They proved to be a good match for the Plains Indian. Another interesting detail in the painting is shown on the far horse in the distance on the right. You can see a symbol painted on the horse’s flank near the tail. The symbol signifies the number of horses the rider owns or how many he has stolen, “said Mary.

“I didn’t know that,” I replied.

“Stealing horses from other tribes became a common practice. The 1700’s was the age of the horse for the Plains Indians. The horse changed Indian culture in many ways, some for the better, making it easier to transport possessions and hunt, but in other ways the horse created tensions, less equality and more warfare between tribes,” said Mary.

“In a sense, the horse represented a new technology for the Indians and with any new technology you can expect change,” I said.

Mary and I walked on through the exhibits and stopped at a sculpture executed by Cyrus Dallin entitled the “Appeal to the Great Spirit”. The sculpture was a large white plaster cast used to create bronze replicas sold by the artist.

Cyrus Dallin was born to pioneers on November 22, 1861 in Springville, Utah. As a youth, he had many friends among the local Ute Indian tribe. His Ute friends showed him how to make sculpted clay animals, which sparked an interest in art. At nineteen he boarded a train on his way to Boston, and met the 1880 Crow Indian delegation on their way to Washington DC to meet with government officials. Dallin became friends with the Crow delegation and the chance meeting made a deep impression on the young man. Dallin never forgot the Indians. As an adult, he used his understanding of the Indians, and their plight to create his artwork. A plaque at the Rockwell Museum contains the following quote explaining his art:

“synthesize in simple and impressive symbols the tragic history & the pathetic destiny of the aborigines of America”.

The “Appeal to the Great Spirit” was the last of a series of four scultptures he created to illustrate this idea.

“Dallin understood the Plains culture. He realized that the stereotypes of Indians as savages were untrue and tried to change the image of Indians through his artwork,” said Mary.

“The history of the Indians is filled with tragedy,” I said.

Not far from Dallin’s “Appeal to the Great Spirit” stood a sculpture by James Fraser entitled “End of The Trail” an iconic image of a vanishing race. Fraser’s father, Thomas Fraser, worked for railroad companies in the West that built rail lines into Indian territory. Also, he was part of a group sent out to recover the bodies of the soldiers of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, which General Custer had led to their demise at their famous encounter with the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho during the Battle of the Little Bighorn. His son, James, was born a few months before the historic battle. As he grew up, he saw firsthand how the Indians were pushed further and further west and finally confined to Indian reservations. Mary and I turned our attention to the bronze sculpture he created.

“Today there is a huge resurgence in native languages, traditions and education of tribal culture among the American Indians. Many Native Americans do not like this sculpture because they feel it shows a defeated, subjugated people. The artist meant the sculpture to represent the tragic plight of the Indians,” Mary said.

“It’s interesting how different people see a work of art based on their own personal preconception,” I said.

“Many Indians come through the museum and it’s interesting to speak with them and discover their perspective on the artwork. The museum also hosts selected Indian artists for special exhibits,” said Mary.

“That does sound fascinating,” I said.

“There were hundreds of different tribes across North and South America; however, through stereotypes in the media most people think of Indians as wearing war bonnets and carrying tomahawks. The Indians have long battled to retain their individual cultures and religious beliefs. After the Indian wars, they were pushed onto reservations and many Native American children were forced to attend boarding schools planned to assimilate them into Anglo American culture. Currently, a big issue among Indians is the concept of Blood Quantum,” said Mary.

“I never heard of that,” I replied.

“The Bureau of Indian Affairs requires that for a person to be considered an Indian he or she must be able to prove a percentage of Indian ancestral blood. It has caused a hot debate among the Indians themselves,” said Mary.

“I guess the core question seeks to answer what is an Indian; genetic or cultural,” I replied.

“I suppose time will tell,” said Mary.

I thanked Mary for showing me the works of art at the Rockwell Museum and left with a broader understanding of what the artwork represents. As I walked past the paintings depicting Indians on spirited horses I wondered what the future would hold for the Indian tribes of America.

Note: This is the end of the second blog on the Rockwell Museum of Western Art. Watch for the next blog on the museum: Cowboys at the Rockwell Museum of Western Art. Happy trails to everyone, Pat

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plains_Indians#cite_note-3, http://content.statelib.wa.gov/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/ellensburg&CISOPTR=291&CISOBOX=1&, http://www.media.utah.edu/UHE/d/DALLIN,CYRUS.html,

http://bronze-gallery.com/sculptors/artist.cfm?sculptorID=65, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Earle_Fraser_(sculptor), http://www.allthingscherokee.com/articles_gene_040101.html, http://www.native-languages.org/blood.htm, “The American West”, People, Places, and Ideas by Suzan Campbell

Artwork credits: (from left to right) “The Buffalo Hunt” by Willian Leigh, “The Chief’s Visit” by John Hauser, “Sun River War Party” by Charles Russell, “On the War Path” by Cyrus Dallin, “Appeal to the Great Spirit” by Cyrus Dallin, “End of the Trail” by James Fraser