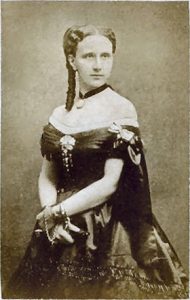

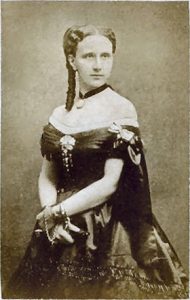

Clara Barton, the youngest of five children, born to Captain Stephen Barton and his wife Sarah on Christmas day 1821 in Oxford, Massachusetts. At the time of her birth, her siblings ranged in age from 17 to 11 years old, making Clara truly the baby of the family. By the time Clara was five she found herself surrounded by adults and teenagers, which lent to her feeling uncomfortable and shy with children her own age.

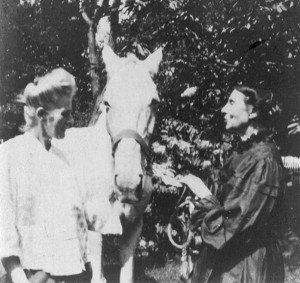

The Barton family lived on a large farm; Clara’s father also bred and sold horses. She learned to ride at age five when her brother David picked her up and placed her on a young horse, broken only to a halter and bit. Once David put Clara on a young colt, he jumped on another and the two galloped off across the fields.

Sometime later when she was ten; her father gave Clara a brown Morgan horse named Billy. Her agility in the saddle increased along with her sense of adventure. She rode in all kinds of weather, often out-riding her companions; leaving them ‘in the dust’, far behind.

Around the age of nineteen, Clara became a school teacher. Her father recognized that teaching placed a heavy emotional burden on his daughter. To help her relax and take her mind off her job; he gave Clara a spirited saddle horse. She often saddled her horse and rode alone, galloping through the wooded country lanes and forgetting the stress teachers often feel. On other occasions Clara rode with her daredevil cousins and friends.

Clara taught school for many years; establishing good rapport with her students; influencing the rowdy boys who attended her classes to focus on their studies. Her students came to admire and respect her; many of the boys she would meet again on the battlefields of the Civil War. When the union soldiers, wounded and dying saw Clara coming to their aid; they thought they saw an angel. Soon Clara came to be known as the ‘Angel of the Battlefield’.

Before the Civil War started in 1854; Clara moved from teaching to a job in Washington, DC with the US Patent Office. In 1857, President Buchanan opposed women working in government and eliminated her position. However, when President Lincoln came into office she was reinstated; although, at lower pay.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, troops from Massachusetts, New Jersey and Herkimer County, NY came to Washington, DC; more than 75,000 soldiers camped in the capital district. Clara meet many former friends and pupils among the troops and resolved to help with the war effort.

Realizing that the government had sadly overlooked medical needs of the wounded; she actively solicited supplies. Women sent her clothing, soap, material for bandages, canned fruit and whatever else they could ship to meet the soldier’s needs. At first, Clara stored the goods in her apartment but when she found herself overwhelmed by the boxes rented space in a warehouse. She used a wagon to transport the supplies to hospitals, ships and trains loaded with wounded men from the battlefield.

As the war raged on, Clara was granted permission to make her way onto the battlefield with her supplies. She aided doctors with the wounded and nursed the dying; helped transport the injured by ambulance wagons to distant hospitals.

Near the end of the battle of the Second Bull Run near Manassas, Virginia Clara assisted in loading the wounded onto a train headed for hospitals in Washington. A few rebel scouts appeared in the distance then disappeared. A Union officer rode up to Clara and asked if she could ride a horse bareback. After answering “yes” he shouted, “Then you have another hour. ” Clara realized that she would have to ride bareback an unfamiliar horse many miles through enemy lines to reach the capital. There would be many times when Clara would have to race for safety on a Calvary steed, but not this time. Fortunately the men were quickly loaded onto the train. Clara and the other workers leapt into the boxcar as the engine quickly pulled away from Fairfax Station. As she watched from the train, Confederate horsemen galloped to the station and burned it to the ground.

In 1863, David Barton, Clara’s brother, received an appointment from the Senate as a quartermaster. Towards the end of March, David received orders to report to Hilton Head, South Carolina. Clara received permission from the War Dept. to accompany him on their mission to join the 18th Army Corps which prepared to bombard Fort Sumter. Stationed on the Sea Islands, a chain of narrow lands cut by marshes and creeks with many inlets; the Bartons found little military action and light duty.

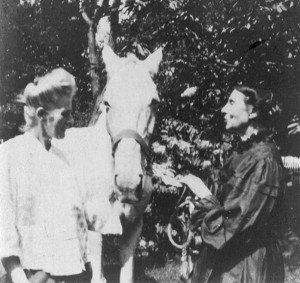

Clara met and became romantically involved with Colonel Elwell; quartermaster in charge of horses, equipment and supplies. They shared a love of horseback riding; both exceptional equestrians. With access to the best horses in the army’s stables, they galloped along the beach as waves splashed against their horses hooves; often stopped to pick blackberries astride their mounts and occasionally chased sea turtles across the sandy shore. Totally infatuated, they wrote poems and love letters to each other; disregarding the gossip their relationship created.

At Hilton Head, Clara also met Frances D. Gage and her daughter Mary. The Gages came from Ohio to take charge of one of the contraband plantations on Parrish Island. Frances, the mother of eight children, advocated for feminism, temperance and the abolition of slavery. She wrote articles for The Ohio Cultivator under the pen name Aunt Fanny. Clara volunteered to help Frances with the freed blacks; taught reading and brought gifts of clothing and food. Long after Clara left the Sea Islands she would fondly remember Frances and all she learned from her.

At Hilton Head, Clara also met Frances D. Gage and her daughter Mary. The Gages came from Ohio to take charge of one of the contraband plantations on Parrish Island. Frances, the mother of eight children, advocated for feminism, temperance and the abolition of slavery. She wrote articles for The Ohio Cultivator under the pen name Aunt Fanny. Clara volunteered to help Frances with the freed blacks; taught reading and brought gifts of clothing and food. Long after Clara left the Sea Islands she would fondly remember Frances and all she learned from her.

The arrival of General Gillmore quickly changed things; he organized the troops in an attack on Fort Wagner situated on Morris Island. Clara saddled her horse, packed an ambulance with supplies and headed for the battlefield. Meanwhile, Colonel Elwell prepared for battle. A battle which led to his injury as well as many causalities sustained by the troops.

Clara and Mary Gage assisted the surgeons and nursed the fallen soldiers. After Colonel Elwell recovered, he too attended to the wounded. Although the troops lacked adequate supplies and provisions; General Gillmore pushed his men forward. He eventually managed to capture Fort Wagner and Fort Sumter, however, never gained access to Charleston.

After the war, Clara helped locate missing soldiers and marked thousands of graves with the names of the fallen. Then, she set out on the Lyceum lecture circuit; talking about her experiences during the war and women’s rights. Speaking to audiences throughout the country, catapulted Clara to national fame. During this time, she meet Fredrick Douglas, Susan B Anthony, Elizabeth Stanton and many others involved in movements for women’s rights and the fight for black enfranchisement and equality. By 1869, Clara found herself exhausted and in poor health. Following her doctor’s orders, Clara set sail for Europe to recuperate.

She traveled throughout Europe. In Geneva Switzerland, Clara met the Grand Duchess Louise of Baden during the Franco-Prussian War. She helped organize military hospitals and sewing factories for women working for the war effort. After the war, Emperor Wilhelm awarded her the Iron Cross of Merit. Clara and the Duchess remained lifelong friends.

She traveled throughout Europe. In Geneva Switzerland, Clara met the Grand Duchess Louise of Baden during the Franco-Prussian War. She helped organize military hospitals and sewing factories for women working for the war effort. After the war, Emperor Wilhelm awarded her the Iron Cross of Merit. Clara and the Duchess remained lifelong friends.

In Switzerland, Clara learned about the International Red Cross and dedicated the rest of her life to establishing the organization in America; writing pamphlets, lecturing and lobbying politicians. Finally on May 21, 1881, the American Association of the Red Cross was formed and Clara was elected President.

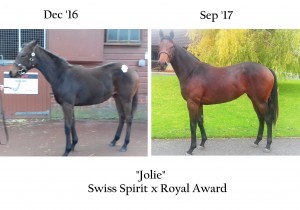

For some years, Cuban revolts against Spanish rule aroused the interest of the United States. The U.S. backed the Cuban rebels. When the USS Maine, a Navy armored cruiser, mysteriously exploded and sank in Havana Harbor; the U.S. declared war. At the start of the Spanish–American War, Clara age 77, traveled to Cuba to set up Red Cross stations. The stations provided provisions and medical help for both sides of the conflict. Her last horse, Babe, was given to her in Santiago, Cuba during the war by a correspondent of the New York World.

Clara set-up Red Cross emergency stations during times of natural disasters such as forest fires, earthquakes, floods and hurricanes. She organized the relief for the 1884 flood on the Ohio river, the 1887 Texas famine, 1888 Illinois tornado and Florida yellow fever epidemic. At the Johnstown Flood in 1889, 50 doctors and nurses responded to the disaster. In 1900, she came to the aid of Galveston hurricane victims and established an orphanage. During all these emergencies, Clara personally visited, directed and helped at the disaster site; managed the operations of the Red Cross at the scene of the disaster; not from behind a desk at headquarters.

Times change; as the Red Cross grew into a national relief organization, some board members began to feel the need for new leadership. In 1902, Mabel Thorp Boardman led an internal rebellion to overthrow Barton as president of the American Red Cross. The dissent succeeded and Barton left the Red Cross in 1904. At that time, Clara proposed that the Red Cross establish a training program for first aid; however, she was overruled.

By this time, Clara, although angry and humiliated, became resigned to retirement at age 83; however, that was not to be the case. Edward Howe approached her with the idea of establishing a non-profit organization for teaching first aid. In 1905, they established the National First Aid Association of America, with Clara honorary president. The group developed the first, training programs and first aid kits designed for fire departments, schools, churches, community groups, factories and ambulances. Their hope was to have a training program in every American town. The organization rapidly grew; establishing training programs across two-thirds of America.

In 1908, the society faced a serious challenge from the Red Cross. Under the leadership of Mabel Boardman, the Red Cross moved to take over the First Aid Association. This action on the part of Red Cross reinforced Clara’s earlier feeling that Boardman sought to expropriated associations when well established. Although, the First Aid Association administrators wished to fight the Red Cross takeover; Clara counseled against litigation. Her personal experience sited the enormous political power behind Boardman and the Red Cross. In 1909, the First Aid Association disbanded after the War Department backed first aid training by the Red Cross.

After being forced from the Red Cross and the demise of the First Aid Association; Clara retired to write an autobiography at her home in Maryland. She wrote ‘The Story of My Childhood’ published in 1907 while still working for the First Aid Association and intended to write a complete book on her life; but never did.

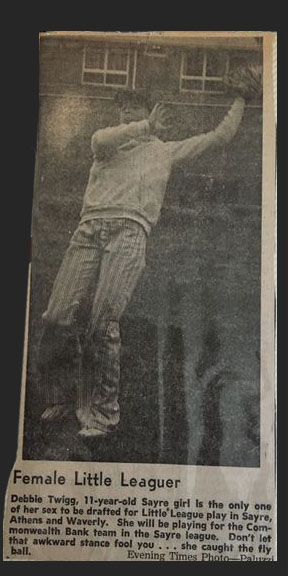

Clara didn’t always have an easy time; many times people tried to prevent her from moving forward with her patriotic humanitarianism and determination to help wounded soldiers, bring needed supplies onto the field of battle, aid natural disaster victims and set up the Red Cross in America. Some said it wasn’t a woman’s place and wished to be rid of her; even so others supported her effort.

Clara, an expert rider, owned many horses and enjoyed riding all of her life. Would Clara have founded the Red Cross if she hadn’t been a skilled horsewoman? Probably not, since riding enabled her to go onto the battlefield, bring medical supplies and aid to the wounded. In addition, learning to ride gave her a sense of adventure and accomplishment which helped her fulfill her patriotic vision of aiding in times of war and disaster. Babe, her final horse, lived at Glen Echo with Clara until Clara’s death at 91 in 1912.

Note: Sometime shortly before her death, Clara cut a hole in the wall of her home at Glen Echo. She stuffed her personal papers and journals inside and covered the hole. Her house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966; later in 1974 the house became the Clara Barton National Historic Site . During a renovation of the building a wall was torn down and Clara’s personal writing and memorabilia were discovered. The new information on Clara Barton’s life became available to the public. Elizabeth Brown Pryor utilized this information as well as other sources to write ‘Clara Barton Professional Angel’ published in 1987. Much of the information and interest in writing this article stemmed from reading Pryor’s book. The book is well written and researched besides being an enjoyable read. I highly recommend it if you want to learn more about Clara Barton. Happy Trails

Sources: https://civilwartalk.com/threads/clara-barton-animal-lover.134833/; Clara Barton: A Centenary Tribute to the World’s Greatest Humanitarian by Charles Sumner Young; https://www.tampapix.com/barton.htm; http://www.clarabartonbirthplace.org/claras-life/claras-family/; https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/clara-barton; https://www.nps.gov/clba/learn/historyculture/upload/cbservice.pdf;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clara_Barton; https://womenwordswisdom.com/2012/12/22/clara-barton-on-weaving-with-flying-fingers/; https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/clara-barton; https://civilwartalk.com/threads/clara-barton-animal-lover.134833/;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clara_Barton; https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/clara-barton;

http://www.spanamwar.com/Barton.htm;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clara_Barton_National_Historic_Site

https://www.wdl.org/en/item/7315/

Book – Clara Barton: Professional Angel by Elizabeth Brown Pryor, 1987, University of Pennsylvania Press. pgs 95, 79-86, 110-118, 120-123, 134-137, 159-171, 357-364

Copyright © 2019 Patricia Miran All Rights Reserved

Time has a way of speeding by you if you’re not careful. Before you know it, summer is gone and autumn arrives with finality. We have had a nice stretch of riding weather and the landscapes have been extremely beautiful; a lot due to the warmer weather and abundant rain; keeping the grass greener than green. Yet the nights have been cool letting the trees change into their annual coat of fall colors.

Time has a way of speeding by you if you’re not careful. Before you know it, summer is gone and autumn arrives with finality. We have had a nice stretch of riding weather and the landscapes have been extremely beautiful; a lot due to the warmer weather and abundant rain; keeping the grass greener than green. Yet the nights have been cool letting the trees change into their annual coat of fall colors.